Draft, Hunsinger, Ives and Nethercott Win Vermont Book Awards

Updated Monday, May 5, 1:45 p.m

Vermont authors Margaret Draft, Emma Hunsinger, Lucy Ives and GennaRose Nethercott have won 2024 Vermont Book Awards. The winners of Vermont’s highest literary prize were announced on Saturday at Vermont College of Fine Arts in Montpelier.

Each wins $1,000 and a cowbell trophy created by Walden master jeweler and metal artist Nikki Ibey. The prize, administered by the Vermont Department of Libraries and Vermont Humanities, was given in four categories for work published in 2024.

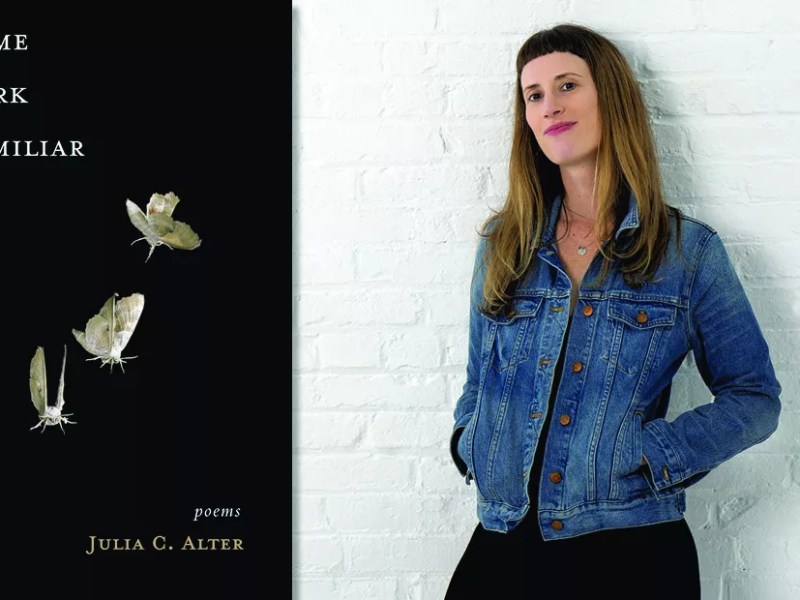

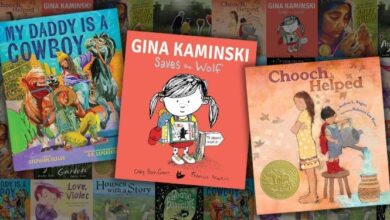

Draft won the poetry prize for her debut collection, Nowhere Was a Lake; Hunsinger won the children’s literature award for her first published graphic novel, How It All Ends; Ives won the creative nonfiction award for her collection of essays An Image of My Name Enters America; and Nethercott won the fiction prize for her short story collection Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart and Other Stories.

The winners were selected from a field of 15 finalists.

Noting these “truly difficult days” as President Donald Trump seeks to disband the national agencies that support the arts, humanities, museums and libraries, Vermont Humanities executive director Christopher Kaufman Ilstrup opened the awards ceremony by reading the poem “Instructions on Not Giving Up,” by U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón.

Keynote speaker Bill McKibben said he initially intended to talk about how much fun it is to be a writer in Vermont, but recent news has made him somewhat paranoid. “I even started compiling a list for you of all the great volumes to be read in prison and stories about all the good books that have been written there,” he said.

We “are in very serious trouble,” the author and climate activist continued, “and that means we need very serious and very funny and very rude and very skilled guides out of that trouble. In a working culture, writers play that role.”

Accepting the award for poetry, Draft said that she spent 10 years writing the works in Nowhere Was a Lake, which was inspired by the Bennington farm that has belonged to her family for six generations. Writing, she said, shares a similar aspiration of continuity: “At our core, writers are caretakers. We’re gently guiding our readers down and along the page. We are keepers of time, stewards of syntax. We are curators of craft, lexicon, sound, song, image, tone and sentiment.”

Seven Days reviewer Jim Schley called Draft’s collection an “extraordinarily accomplished first book.” Her words “are muscular and flexible,” Schley wrote, and she uses the spaces between lines and stanzas “for temporal, tonal and narrative leaps,” he continued. “Draft’s method is to convey enormity with brevity and restraint.”

Hunsinger, who has an MFA from the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, delighted the audience with her remarks, noting that she hadn’t prepared any because she didn’t expect How it All Ends to win.

“I’m actually a huge loser,” she said. “It takes a really long time to make a graphic novel, but it only takes 45 minutes to read it. So thank you all for spending 45 minutes reading this book.”

Vermont has shaped her perspective on life, she continued. “You really learn a lot when you’re outnumbered by bugs, by trees, by blades of grass, when you get snowed in and the power goes out, and then you’re boiling snow so you can flush your toilet.”

Best-selling author Alice Oseman has called How it All Ends “a whirlwind dive into the chaotic imagination of a tween experiencing her first crush,” while two-time National Book Award finalist Eliot Schrefer deemed the middle-grade graphic novel “imaginative and hysterical, and with the sort of rare clear-seeing honesty that will make any reader feel less alone in the world.”

Creative nonfiction winner Ives also expressed gratitude for Vermont in her acceptance speech. Moving to the state in 2018 was one of her best decisions, she told the audience. “It has produced dramatic changes in my writing, and it’s given me a sense of hope and purpose.”

Ives is a novelist, poet and an assistant professor of literary arts at Brown University. Her five interrelated essays in An Image of My Name Enters America explore identity, national fantasy and history as Ives examines events and records from her own life to excavate larger aspects of the past that have been suppressed or ignored.

In its “Best Books of 2024” roundup, Vulture called the work “part criticism, part personal essay, part intellectual jubilation” and “the most inventive and exciting work of nonfiction this year.”

In Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart and Other Stories, Nethercott “has found shrewd ways of kneading together the weird capriciousness of folk myths, monster fables and ghost tales,” reviewer Schley wrote for Seven Days.

Magical realism, with its ability to mend the dissonance between the real world and one’s perceived reality, is the thread that ties the 14 stories together, Nethercott told NPR in 2024. “When I write a story, I essentially think of it as taking the human experience and turning the volume knob up,” she said.

Nethercott didn’t attend the ceremony. In her prepared remarks, read by writer Robin MacArthur, she noted that writers typically spend years isolated with a glowing laptop screen.

“We spend a lot of time with people we’ve made up,” she said. By contrast, in Vermont, “community is a living, breathing thing,” Nethercott continued, and writers are friends and collaborators. “I consider myself beyond lucky every day to work beside you.”

The Vermont Book Award was created in 2015. Books by writers who live in Vermont for at least six months of the year are eligible as long as their work is not self-published. A panel of judges, composed of writers, booksellers, librarians, educators and other supporters of literature, named the 15 finalists and selected the winners.

Alice Dodge contributed reporting.

This article appears in Apr 30 – May 6, 2025.

Source link