“Strangely, neither Hitler’s nor Godse’s books are banned in India.”: Gautam Navlakha

Writer, journalist, and human rights activist Gautam Navlakha has had a decades-long career spanning journalism to activism. All along, through his writings and rights activism, he has always been committed to democratic rights and social justice for all. He has always stood by, spoken out and written in defence of the marginalised communities whose voices he has sought to amplify throughout his career.

Born in Kolkata in 1952, Navlakha grew up in a household where reading Hindi and English literature was encouraged. His parents encouraged him to read widely. After finishing college in Kolkata, he went on to pursue his higher studies in Sweden and subsequently embarked on a decades long career in journalism and activism. He served as assistant editor and senior columnist at the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) in a long career spanning over 30 years after joining the journal in the mid-80s. During this period, he wrote extensively on the political economy, conflict regions, and state of civil liberties in India.

He has been an active member of organisations defending human rights, including the People’s Union for Democratic Rights. In recent years, he has also faced over four years in jail and under house arrest. He was arrested in the Bhima Koregaon/Elgar Parishad-Maoist links case in April 2020. The Supreme Court granted him bail in May 2024. His major works, in addition to hundreds of analytical pieces published in EPW over more than three decades, include Days and Nights in the Heartland of Rebellion (Penguin India, 2012), which offers a first-hand account of the Maoist movement and state violence in Bastar, and War and Politics: Understanding Revolutionary Warfare (Setu Prakashani, 2014). Navlakha has also extensively written about militarisation in Kashmir and Chhattisgarh in leading publications, journals and anthologies.

In this interview, Gautam Navlakha reflects on the importance of books in his life, the kind of books he read during his jail time, where reading became a source of intellectual freedom and resilience, why he thinks publishers should make books affordable to sustain reading culture, and how banning books and censoring authors is a regressive trend. Edited excerpts:

How important were books and reading to you while growing up?

I was lucky. My father was well-read and highly educated, while my mother, though not even a matric pass, was immersed in Hindi literature. I had both Hindi and English literature around me while growing up. My father introduced me to English books and my mother gave me Hindi classics. My parents also encouraged us to read by subscribing to children’s magazines like Chandamama and Parag. We also use to get Sarita, Sarika, Dharamyug, and Saptahik Hindustan. So reading and graduating to books was not difficult.

So books were an intrinsic part of my life. My appreciation for them is somewhat marred by present realities where these freedoms are threatened. I love reading, and I’m sure many others feel the same way. For me, reading is a communion. When you read a book, you disappear into different voices, and it’s such an enriching experience.

Also Read | We should not be bullied by ‘literary trends’: Sumana Roy

Were there any particular books or authors that influenced you during your adulthood?

Hindi classics, such as the ones from Bankim Chandra, Sarat Chandra, Premchand, etc, played a very important role. We had a complete series at home, which kept my interest alive. Of course, as one grows older, reading tastes evolve and new authors come along. My father loved pulp fiction, so I was introduced to authors like Perry Mason, Agatha Christie, and Max Brand at a very early age. Mystery and suspense novels fascinated me as a child. As I grew older, my reading journey moved through different phases.

How did your educational journey shape your reading habits and interest in activism, involvement in public issues?

My political readings began during college and university years, especially in Kolkata in the 1970s. It was a time of intense social ferment. I became interested in activism and public issues, reading many leftist classics including Marx, Engels, Gramsci, which radically changed my worldview.

Days and Nights in the Heartland of Rebellion offers a first-hand account of the Maoist movement and state violence in Bastar.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

What kinds of history books and authors did you read during that time?

I read not just historians but also writings by Bhagat Singh, Gandhi, Nehru, Tagore, and Subhas Chandra Bose. These classical texts were crucial to my reading. I became more deeply engaged with history later.

Which books and authors did you discover and enjoy reading during your university education in Sweden?

I did my graduate and post-graduate studies in Sweden. There, D.D. Kosambi had a great impact on me, especially his books such as Culture and Civilization of Ancient India and An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, and his essays in Myth and Reality. I was introduced to D.D. Kosambi by my Professor in Sweden, who was the son-in-law of D.D. Kosambi. And he helped us with the study group, which was formed. Kosambi’s Marxist analysis was thought-provoking and comprehensive. His lucid writing made complex history accessible even to amateurs. Many of my generation back then were reading these authors. I always liked reading about Indian history from multiple perspectives, as well as economics.

Tell us about your initial years after joining EPW. How did your editorial work influence your reading habits as a journalist, editor, and later as an activist?

My first job was at Economic and Political Weekly in January 1980, starting as an assistant editor. Part of the job was to read and mark 10–11 newspapers every day and plan editorial commentary. This kept my reading broad and deep, but also different than sustained book reading. Initially, for the first 5-6 years, it was mostly office work. Later, after moving to Delhi, I became more active in civil liberties organisations and travelled more, and that pattern continued into the 1990s and beyond. I resigned my formal association with EPW in 2013 after 33 years, though I continued contributing. EPW was my mentor in many ways.

How did your reading choices change as you moved into journalism and activism roles?

Book reading declined as I started reading far more newspapers, journals, and academic articles. There were piles of them to sort every day. Still, books never left me entirely, even if the sustained book reading of my youth wasn’t possible.

Did you start reading more during your jail confinement and incarceration period post-COVID outbreak in 2020?

Yes, my time in jail brought me back to books in a very deep way. Reading helped ease pain and suffering. Everyone inside jail reads all kinds of books—from pulp literature to serious, thought-provoking works. Friends, especially one close friend, would supply me with interesting books.

My fellow co-accused, in particular, and several inmates and I would share the books amongst us. Family and friends kept providing books, after a struggle with jail authorities to allow us to receive books. I was fortunate to be allowed access to the jail library, unlike other inmates who were denied access. Which tells its own story of denial/access regime inside the jail. I had plenty of books to read.

Can you name some books you particularly liked reading during your jail time? What was about these books that resonated with you?

One book I read in jail was by a holocaust survivor, Viktor Frankl, whose book, Man’s Search for Meaning, a thin one, helped me enormously during captivity. He dealt with his brutal incarceration by following the precept that even when you lose everything, we retain our freedom to choose our attitude. It’s when we have a purpose, we can survive extreme distress.

The sole book I had with me during my 11 days of National Investigation Agency custody in a windowless cell was Tony Joseph’s Early Indians, which I highly recommend. The book was like a mind opener which took me on a journey, even as I was confined to a cell, into our past, dating back to 60,000 years. It connected me to the world outside. Another book I read in jail was Peggy Mohan’s Wanderers, Kings, Merchants. Reading these books felt like an intellectual liberation and gave me mental freedom in a confined space.

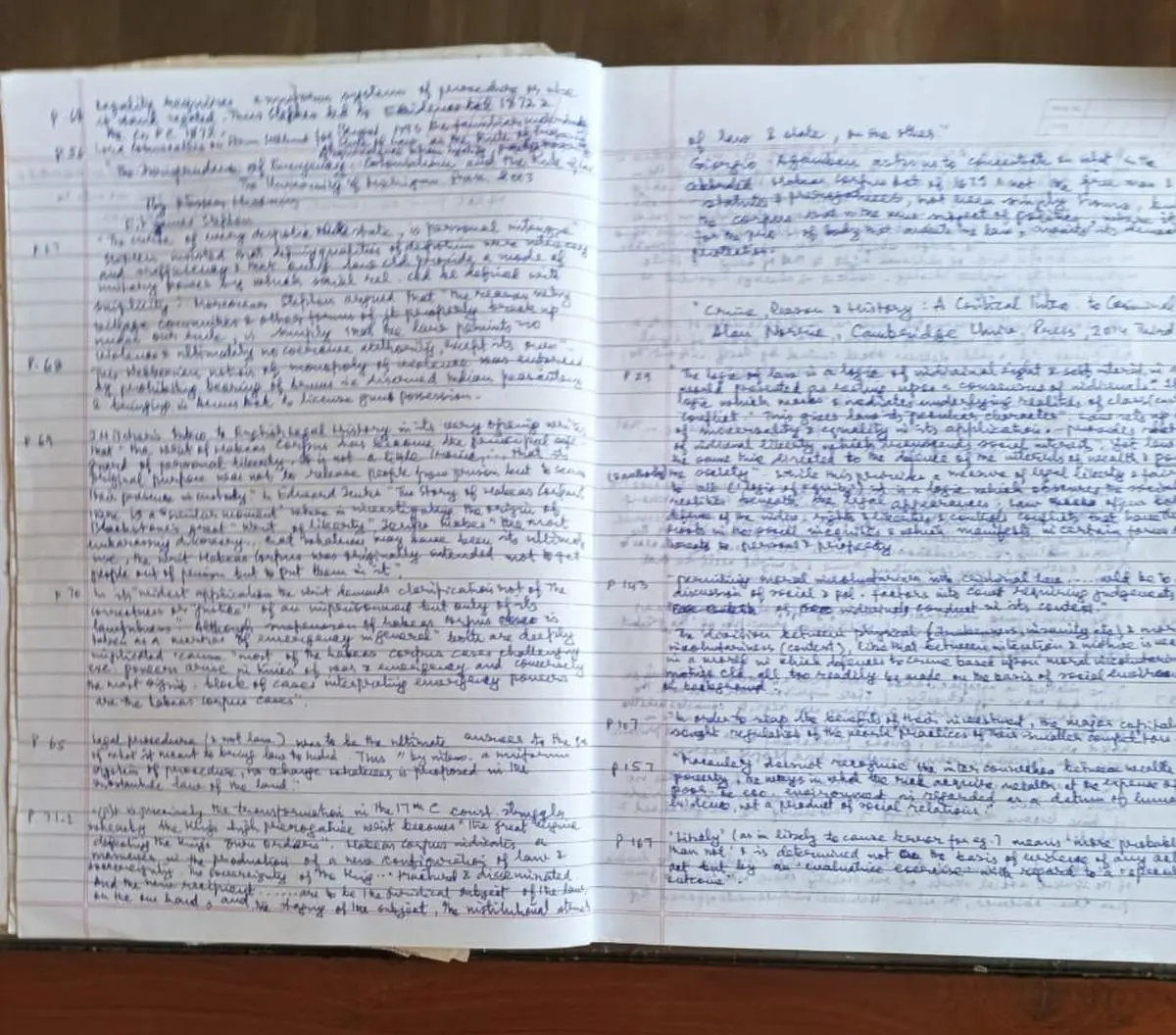

Inside pages of Gautam’s diary filled with entries of books etc, read inside prison.

| Photo Credit:

Photo courtesy Gautam Navlakha

What makes a book stand out for you now?

The books that stay with me are those that are well-researched and well-written. If the author has clarity, it shows in their writing. Making ideas accessible is important. That’s the standard I aim for in my own writing as well. Books remain integral to my life, even if the way I read has changed over the years. Different phases and circumstances bring different rhythms to reading, but curiosity and a love for books endure.

Did you take notes in your diaries from your readings in prison?

Yes, I take notes in diaries and registers, especially when a book makes an impression. I keep these records as part of my ongoing engagement with books. I took notes when I found a book particularly interesting. I have two or three registers filled with these notes.

Any other reading that left a lasting impression on you during your jail time?

The reading I did in jail was very diverse. One particular book that really struck me was a collection of articles from the journal Modern Review, which was published from the 1920s to the 1940s and played a significant role in India’s freedom movement. It was a platform where intellectual giants like Tagore, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Nehru, among others, contributed. The debates it hosted, such as the Gandhi-Tagore discussion on nationalism, were fascinating to confront inside jail.

Recommend a few books that you have liked reading recently. And how have these works influenced you?

This is a difficult question because there are far too many books which I appreciate. However, since space is a constraint, let me cite a few. I would particularly like to recommend my dear friend Uma Chakravarty’s recent book, The Dying Lineage: The Crisis of Political Power in the Mahabharat. It traces the transition from kin-based chiefdoms to monarchical kingdoms and focuses on the link between class, caste and gender in a stratified society. It vastly enriches our understanding of our past. To read the Mahabharat after reading this book provides an altogether different level of understanding.

Having experienced jail, prison literature has a particular interest for me. Two books were particularly profound. The first one is A Naxalite`s Prison Diary: 13 years, by Ramadhar Singh. His account of prison life is a simple and straightforward account based on his observation and reflections which makes it profound.

The other book is Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, & Reparations | Chicago to Guantánamo edited by Amber Ginsburg, Aaron Hughes, Aliya Hussain, and Audrey Petty. It is a collection of artwork by Guantanamo prisoners who used styrofoam cups, toilet paper, cartons, etc, to draw, paint, and write poetry. Often and repeatedly, their artworks were destroyed, but the prisoners didn’t give up and persisted and carried on. The interviews and selection of the artworks spread through the book is one of the most remarkable feats of human endurance and fight-back to reclaim their humanity and freedom.

The cover of Navlakha’s book War and Politics: Understanding Revolutionary Warfare. He has also extensively written about militarisation in Kashmir and Chhattisgarh in leading publications, journals and anthologies.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Do you think the space for book reviews and overall book coverage is disappearing from the mainstream Indian press? It seems that many Indian newspapers and magazines dedicate little or no space to books these days. What are your thoughts on this trend?

I don’t believe that the books are going to disappear. I mean, no matter how popular the internet and all becomes, book reading will continue to remain. And it’s very evident from the way in which you discover that even in this day and age, books are doing well. It’s a different matter that the print media no longer, barring The Hindu and one or two other newspapers, no other newspapers in the Sunday or weekend section anymore carries book reviews or covers the books beat regularly.

The fact is that newspapers don’t carry pieces on books and cover books extensively anymore. They live in this illusion that the books don’t matter as much. Maybe they believe people have stopped reading books and books don’t matter as much now.

The prices of books are also going up, which is worrying. One has to think about it. The publishers actually ought to think of it because you can not promote books by pricing them out of reach. You have to make them available at a reasonable price in larger numbers. That is what they ought to be pushing for, rather than creating a niche by hiking the book prices. I mean, this doesn’t make sense to me as a book lover. In fact, it means that the culture is actually regressing very fast. And that’s a sad reflection of our current contemporary reality—the regression of culture, literary, or education. The times when I grew up, this was not the case.

Also Read | Eagerness to be near books still drives my love of reading: Junot Díaz

Talking of books, how do you view the recent government-enforced ban on 25 selected books in Jammu and Kashmir in the broader context of restrictions on freedom of expression and the state of intellectual discourse in India?

I find this books ban alarming. I feel outraged. The fact that books can be proscribed wholesale, even as we are talking about books. This is a part of the regressive course India seems to march on, unmindful of its consequences. It should be left to the readers to form their own opinion. This business of imposing a choice on us or denying us the right to form our own view is, to say the least, senseless. Strangely, neither Hitler’s nor Godse’s books are banned in India. Carl Sagan once wrote, “books break the shackles of time”. I would add: also borders and boundaries. This trend of banning books and censorship is a clear mark of a nation in decline.

Majid Maqbool is an independent journalist and writer based in Kashmir. Bookmarks is a fortnightly column where writers reflect on the books that shaped their ideas, work, and ways of seeing the world.

Source link