How a Broken Heart in Brussels Turned Charlotte Brontë into the First Modern Feminist Author | Books

Premium

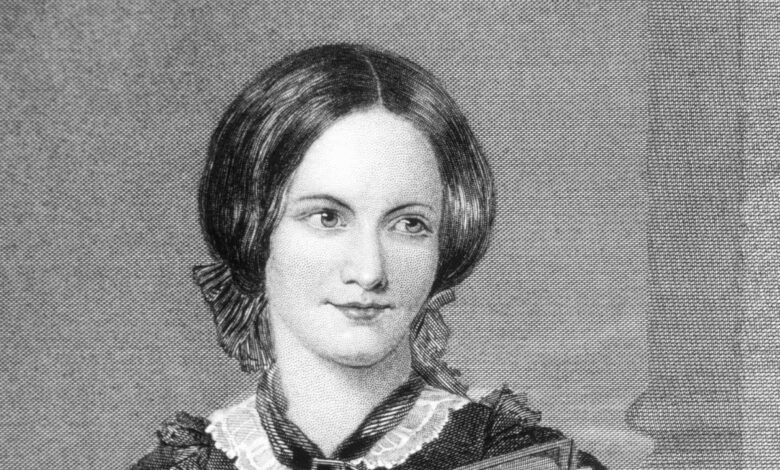

Heartbreak in Brussels turned Charlotte Brontë from a quiet teacher into a fearless literary voice. Her unrequited love for her mentor inspired ‘Villette’, a story of solitude, strength and self-discovery. In transforming pain into power, she shaped a new kind of heroine and became one of history’s first modern feminist authors.

How a Broken Heart in Brussels Turned Charlotte Brontë into the First Modern Feminist Author

In the cold winter of 1843, Charlotte Brontë found herself far from the windswept moors of Haworth, standing in a dim classroom in Brussels and confronting a truth she could no longer ignore — that the life she expected was not the one she would live. A schoolmistress in a foreign land, isolated, longing and deeply aware of her limitations, Charlotte began to write not just from anger, but from power. What emerged was a novelist who would not only upend the literary norms of her age but also become a voice for women’s unspoken ambitions. Her time in Brussels was not simply a detour in her biography. It was the crucible in which she shaped her convictions, sharpened her voice and transformed heartbreak into enduring art.

Charlotte Brontë was born on 21 April 1816 in Thornton, Yorkshire, the third of six children of Patrick Brontë, an Irish-born Anglican curate, and Maria Branwell. After the death of her mother in 1821 and the tragedy at the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge, Charlotte’s early life was framed by responsibility, literary ambition and a sense that conventional women’s paths were confining.

In 1842, she accepted an invitation to join her sister Emily in taking up a place at the boarding school in Brussels run by Monsieur and Madame Heger. There she taught English, while Emily taught music, in return for board and tuition. The idea was that the sisters could improve their language skills and perhaps open their own school in Haworth one day.

When Charlotte returned alone to Brussels in January 1843 as a teacher, the promise of professional advancement collided with cold loneliness and an unexpected emotional intensity. Her relationship with Monsieur Constantin Heger, her former teacher and now employer, became increasingly fraught. Though the exact nature of her feelings cannot be fully known, letters reveal her passionate attachment and deep despair when it was not reciprocated.

Charlotte’s unacknowledged love for Heger and her growing sense of isolation were not simply private woes. They became the engine of her creativity. The sense of displacement, of teaching foreign girls in a foreign land, of longing for connection while trapped in a strict and stranger-filled institution, all seeped into her imagination. Most literary historians accept that the experiences of Brussels formed the raw material for her novel ‘Villette’ (1853).

In ‘Villette’, the protagonist Lucy Snowe travels to the fictional Continental city of Villette to teach at a girls’ school. She encounters alienation, unrequited love, language, the foreignness of everything around her and learns to assert an independence of mind. The figure of M. Paul Emanuel is widely acknowledged to be modelled on Heger.

In Brussels, Charlotte saw how women were expected to educate others, submerge their own longings, and live professionally but invisibly. Rather than submit, she mined the interiority of the woman who was both an outsider and an educator. It is here, in that chilly pensionnat, that she began to reframe what female ambition could mean.

Rewriting the Feminine Narrative

While her earlier novel ‘Jane Eyre’ (1847) had already struck revolutionary chords with its first-person female narrator declaring her own worth and heading into marriage on her own terms, ‘Villette’ pushes further. In it, ‘Charlotte’ gives voice to psychological nuance, displacement, cosmopolitan identity and the cost of emotional labour.

Her portrayal of Lucy is neither a flawless romantic heroine nor a passive victim. Lucy is wry, guarded, and emotionally complex. She observes the world of others and asserts her own interior existence. Scholars such as Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar have noted that Villette explores gender roles and repression in unexpected ways.

The Brussels experience, therefore, was not just background. It introduced Charlotte to the raw materials of feminist inquiry: a foreign land where a woman must establish herself; a teaching post that is respectable yet constrained; a failed romance that erodes illusions and forms resolve. Over time, Charlotte seized control of her narrative: women could feel, think, teach, and act.

Professional Self-Assertion

Returning to England in 1844, Charlotte brought with her the seeds of a writer transformed. Her rejection of the conventional future for women, manifested in her refusal to be content with conventional domesticity, emerges clearly in her fiction. She left Haworth only rarely, yet her imagination travelled further than many men’s of her age.

Her career accelerated: ‘Jane Eyre’ was published to acclaim in 1847 under the pseudonym Currer Bell. The use of a male pseudonym signals how women had to navigate a male-dominated literary world. Yet the novel’s radical insistence on the hero’s moral equality and the heroine’s psychological self-definition challenged the status quo.

By the time ‘Villette’ appeared in 1853, Charlotte was writing with full control and confidence. The novel does not flaunt a feminist agenda in modern terms. Instead, it demands that the reader recognise Lucy’s inner world, her labour, her eyes on the foreign horizon, her refusal to vanish. In that sense, Charlotte Brontë emerges as one of the first modern feminist authors: not because she labelled herself so, but because she wrote a woman into existence on her own terms.

Legacy and Literary Impact

Charlotte’s work did not stop with ‘Villette’. Though she died in 1855, aged thirty-eight, she left a legacy that reshaped English literature. Her willingness to map female interiority, ambition, desire and despair into novels that sold widely and stirred critics transformed the expectations for women’s fiction.

‘Villette’, in particular, has been vindicated by modern critics. It has been argued that it surpasses Jane Eyre in psychological depth. Virginia Woolf once called it Charlotte Brontë’s finest novel. The portrait of a woman struggling with isolation and emotional longing, yet carving out a self-sufficient path, speaks even today.

In the wider sweep of feminist literary history, Charlotte’s journey is significant. She did not merely reflect the new possibilities of women’s lives. She embodied them. Her move from Haworth to Brussels, from longing to writing, reflects a shift in consciousness: women could teach, write, set their own boundaries, live and create.

Why the Brussels Episode Matters

It may seem odd to define feminist authorship by heartbreak and exile. Yet in Charlotte’s case, the broken heart in Brussels was also a forging heart. It cut away illusions, revealed the cost of desire, forced professional self-reliance and seeded bold fiction. Without the dislocation of being a woman in a foreign school, teaching English in Belgium, longing, observing, and returning home, Charlotte might never have realised how rich and complicated a woman’s interior world could be when given narrative space.

Brussels taught her that ambition and vulnerability could co-exist. That a woman could write about love without surrendering her intellect. That the ordinary-looking woman could be the centre of a story not simply about surviving, but about living. That is the heart of modern feminism in her authorship.

Here is the giveaway for every reader who cares about literature, women’s lives and the quiet revolutions in books: Charlotte Brontë’s time in Brussels was not a mere chapter in a biography. It was the moment when heartbreak became strength, when the foreign classroom became a laboratory of self-invention and when a woman recognised that teaching others might be the first step to teaching herself. When you open Villette today, you are not just reading a novel about a woman abroad. You are meeting a writer who refused to be invisible, who turned longing into language and who changed what it meant for a woman to write, to feel and to choose. That is the real story of Charlotte Brontë, and it is why she remains, after all these years, entirely modern.

Source link