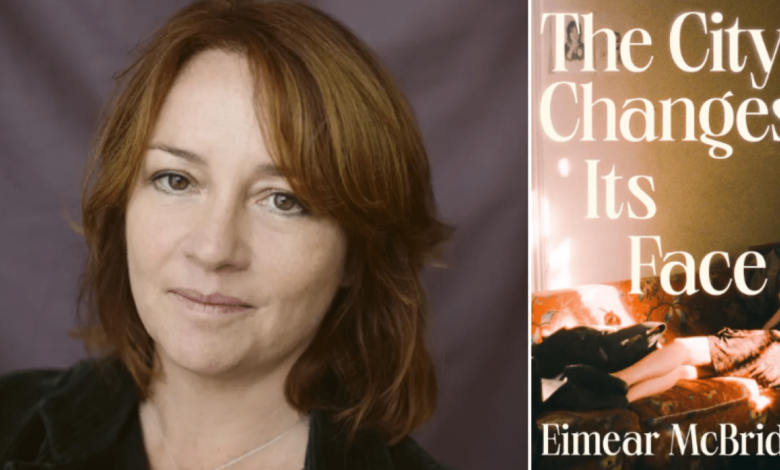

Eimear McBride changed modern literature

‘The City Changes Its Face’ may be more of a mood piece than a novel, but this author shows us how powerful that can be

Eimear McBride has changed modern literature. It took nine years for the Irish novelist to find a publisher for her debut, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing. But once she did – the small Norwich press Galley Beggar picked it up in 2013 – the novel’s rise was unstoppable.

The book won numerous accolades, including the Women’s Prize for Fiction and the inaugural Goldsmiths Prize. Faber bought the rights to the paperback, while its stage adaptation – first at the Corn Exchange, Dublin, then at London’s Young Vic – won plaudits.

The novel – a stream-of-consciousness narrative of one woman’s life, beginning while she is still in the womb, later raging about her experience of rape by an uncle – is emotionally challenging. It’s also formally ambitious. But these successes proved readers do not just want easy fiction. We can deal with the trickier stuff – in fact, we crave it.

In the decade since, McBride’s influence has been apparent: another stream-of-consciousness novel, Anna Burns’s Milkman, won the 2018 Booker; already established authors such as Rachel Cusk and Ali Smith have found wider acclaim with ever more innovative works; and a new generation of formally inventive writers, most notably the Little Scratch author Rebecca Watson, has emerged. (It is no coincidence that all of these authors are women and a number are published by Faber.)

Gladly, McBride’s trailblazing has not halted the forward motion of her own craft. Her latest and fourth novel, The City Changes Its Face – following The Lesser Bohemians (2016) and Strange Hotel (2020) – is a mesmerising account of a relationship on the rocks.

The story is told by Eily, a 20-year-old drama student, who has been in a relationship with Stephen, a 40-year-old actor turned filmmaker, for two years. It’s 1996 in London’s Camden when the cracks begin to show, and the pair look back over their relationship, trying to work out what has gone wrong.

The book holds a dual narrative: the couple in the here and now, with Eily describing Stephen as “he”, and flashbacks to the two previous years, with Eily addressing Stephen as “you”. Often the novel looks like poetry: McBride doesn’t care for speech marks, just the indented plink-plonk, plink-plonk of two characters warring with their words.

A lesser author would make Eily and Stephen’s 20-year age gap the source of their issues. Life isn’t so simple for McBride, whose twist is instead Grace, Stephen’s formerly estranged daughter, just one year Eily’s junior, with whom he is back in touch.

There’s also the staggering trauma of Stephen’s past, which unfolds when he shows Eily and Grace a rough cut of his autobiographical film, which McBride describes in chunks of italicised text: “Exterior. Road. Night. Erratic sound. Images split. The young man runs.” Through these grisly scenes we learn that Stephen used to be a drug addict. He left home young because his mother abused him, and he feared what he would become if he stayed. “‘On and on’ she says. ‘On and on and on. My father to me and me to you and you to…’ ‘No!’” It’s a devastating inclusion.

But lots of the novel’s finest linguistic moments come at comparatively quieter times, such as when Eily learns she is not pregnant and feels “relief at being in my body again by myself”, or when the author describes the sensation of “hop-staggering on the nuisance of gone-to-sleep legs” – something we have all felt yet likely never seen written down with such playful precision.

Throughout McBride’s oeuvre, she asks us to give in to the sounds and rhythms of her language. It’s by this method that The City Changes Its Face is best read. The characters are affecting, but exactly what happens to Eily and Stephen feels beside the point. This novel is a mood piece, and with it, McBride proves yet again how powerful that can be.

Published by Faber on 13 February, £20