Reginald Dwayne Betts’ ‘Doggerel’ transforms his life into poetry • Oregon ArtsWatch

Reginald Dwayne Betts began writing poetry at 17. In solitary confinement at the start of a 9-year prison sentence, he called out for a book, and a volume of poetry was transported to him via pulley system and slipped beneath his door. Now 44, Betts is a MacArthur Fellow, a lawyer, a visiting lecturer at Harvard, and the author of six books, including Felon, which he turned into a one-man theater piece exploring life after incarceration.

“Somebody slid Dudley Randall, the Black poet, underneath my cell door, and I discovered Marvin Harvin, Lucille Clifton, Sonia Sanchez, Sterling Brown, and perhaps most importantly, Etheridge Knight…” Betts told me over the phone in advance of his appearance Saturday at the Portland Book Festival. “I remember thinking, if he can write about prison and make it sing, then I can, too. That is what drove me, and I was chasing a kind of joy — maybe a kind of permission — to be a witness to what was going on. I think I’m driven by questions I want to answer, but also I’m driven toward writing about the joy of the world, no matter where you might be in that world.”

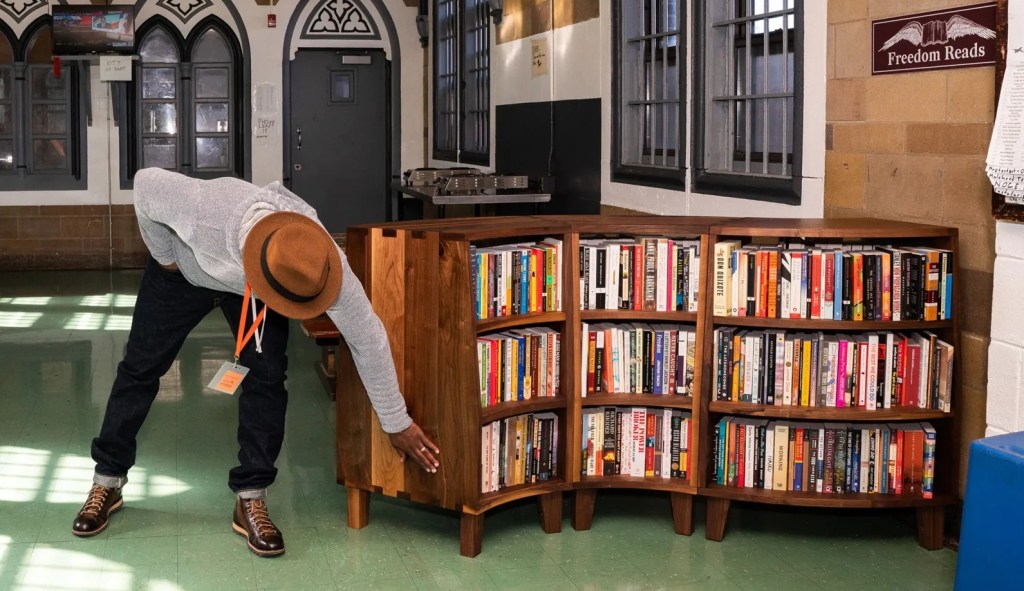

Betts is also the founder of the nonprofit Freedom Reads, a national project and the first of its kind that provides incarcerated individuals with access to books and literature.

“We put millions of people in the prisons — what if we put millions of books in the prisons?” said Betts, who was prosecuted as an adult after committing an armed carjacking at 16. “And what if we did it as a Freedom Library, one cell block at a time, with beautifully handcrafted bookcases that are accessible on each side to create the oasis of literature? That really is the idea for Freedom Reads,” Betts said, adding, “it satisfies a long-standing need. So, we get to bring that to communities, and we get to recognize that sometimes one book will change your life.”

In addition to exposure to books, Freedom Reads provides inmates with resources such as The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison, an anthology and writing handbook by PEN America. Freedom Reads strives to ensure that these library oases, as Betts calls them, contain not only the staples of great literature, but also relatable works and essays written by people who were formerly incarcerated.

“We have my work … so you can study the writers first. I think all of us will say, You study the writers. That’s the first way you become a writer…” Betts continued, “and then you have things like Poet’s Market and Writer’s Market and [others]. Freedom Reads is also about bringing writers into the space so that they can help supply lessons about what it means to be a writer.”

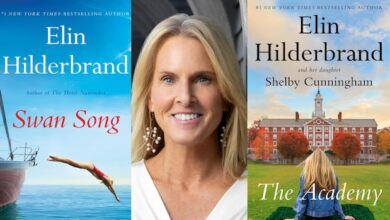

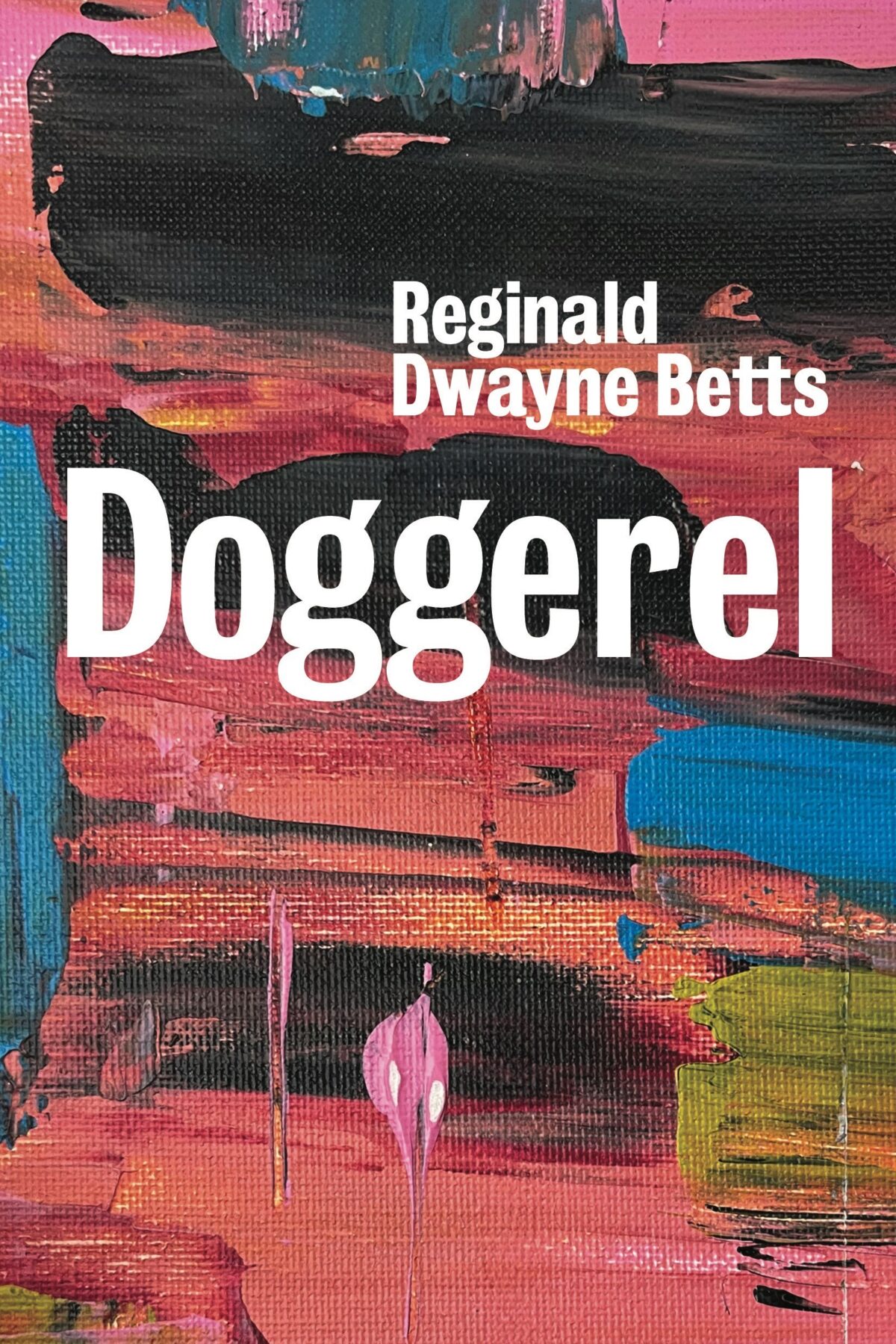

The spirit of generosity and intensity Betts brings to Freedom Reads is the same he brings to his newest book, Doggerel, published in March by W.W. Norton & Co. The collection is a tender and personal work that examines themes of love, vulnerability, masculinity, dogs, and what he calls “the quiet noticing that gives shape to a life.” The title, Betts told me, came partly from the desire not to take oneself too seriously by naming a deeply reflective work after a word whose meaning is “a comic verse composed in irregular rhythm.”

“I chose that because there are a lot of dogs in the book, and I wanted to have a dog running through the title…” he said, “and I wanted to call a very serious book Doggerel, and then give it a sub meaning — my meaning. It’s about a man who learns to walk a dog, learns that he loves dogs, and falls in love. And, you know, in the book are all of those things. It’s about my experience with dogs and with life. It’s kind of a fascinating internal-external portrait of what it means to be me over the last few years of my life.”

Betts will appear at 3:30 p.m. Saturday at the Portland Book Festival, sharing the stage in the Portland’5 Winningstad Theatre with poet Mai Der Vang (see story) in a session called “Shapeshifting.” OPB’s Jenn Chávez will moderate. Advance tickets to the daylong festival start at $18 and are available here.

Your newest book, Doggerel, has been called “vulnerable, meditative, and symbolic.” Do you find that creating the book was a meditation?

Betts: It was, because it was a process of noticing. It was me really trying to deeply immerse myself in a world as I was going through different things in my personal life. And so a lot of times, the poem comes explicitly out of a moment. In the past, the poems I have written haven’t always been about me, even if they were in the first person. Every one of these poems is about me, and so they really represent me living deeply in the world, but also me on some kind of meta level, noticing that living and transforming it into art.

In addition to poetry, you’ve written a memoir and essays. Do those three genres intersect for you?

Only on the level of language … the level of trying to write a good sentence. But whereas the poetry allows me to be inventive and also luxuriate in a single moment, the essay allows me to think. I just wrote an essay for the New York Times Magazine. It’s 6,000 words, but it spans 30 years and lets me write about James Earl Jones and Harry Belafonte, Bill Withers and Michael K. Williams. The essays allow me a lot more time and to think about the world differently.

And what is the correlation between poetry and time?

I think as a writer, in general, you’re in a constant game in which you’re losing time, because when you’re writing, you kind of get lost in it.… I’m glad that I’ve written six books now, because those books are markers of what happened. But otherwise, I can’t wait to forget the days. And so in some ways, you know that the writing is needed to track time and lose time.

Do you feel that the more you write and the more time goes by, you’re less precious about your writing or past books?

I’m more surprised when I like them. I think maybe that means I’m less precious about them because I’ve already, you know, disavowed them. But I’m more surprised when I hear something from [a while ago]. I’m getting better at pacing, understanding, time, perspective, dialog … but sometimes I had an idea from before and I think, “Wow, I’m glad that’s what I was thinking … what the 28-year-old me was thinking…” because, at the end of the day, it’s all in just trying to articulate your thoughts. You get better at the other elements, the craft elements.… I’m just glad some of those thoughts still hold up for me.

You’ve turned your book Felon into a theater production that explores the experience of life after incarceration. What was that process like?

First of all, I had never memorized anything before, so it was literally me saying, “What does it mean to be a playwright and a performer?” And it was arduous and unpredictable. It was timely, even racing in a way, because this is three or four years of my life, and it feels like it just happened, because now I can get on the stage and I can do it. I lost 60 pounds during the process. I got divorced through the process. I raised millions of dollars with Freedom Reads, so we opened hundreds of libraries during the process. There was so much living that happened over the time of that show, and what was amazing about it is that it still happened.

I think what I’ve learned about making a theater piece is that it suits me as a writer. I’m the Walt Whitman kind of writer, where I write the same thing until it can’t be written anymore. And in getting to do a piece of theater, every performance lets you do something that’s slightly different.

What is the importance of literature and literacy in our world today, politically and culturally?

I think [literature] does really give us air. It’s the way in which we learn to breathe. It’s the way in which we learn to understand — not just the world more, and not just our communities more, but literally, it’s the way in which we learn to understand ourselves more. I look at the news, I look around the world, and I feel like one of the things that’s missing is that thing that great theater makes possible.… It’s that we see each other, and that’s what great literature makes possible, too.

Source link